What does South Africa's energy crisis mean for food production?

What is the issue?

Simply put, South Africa is in the midst of an energy crisis, which is limiting the available supply of electricity.

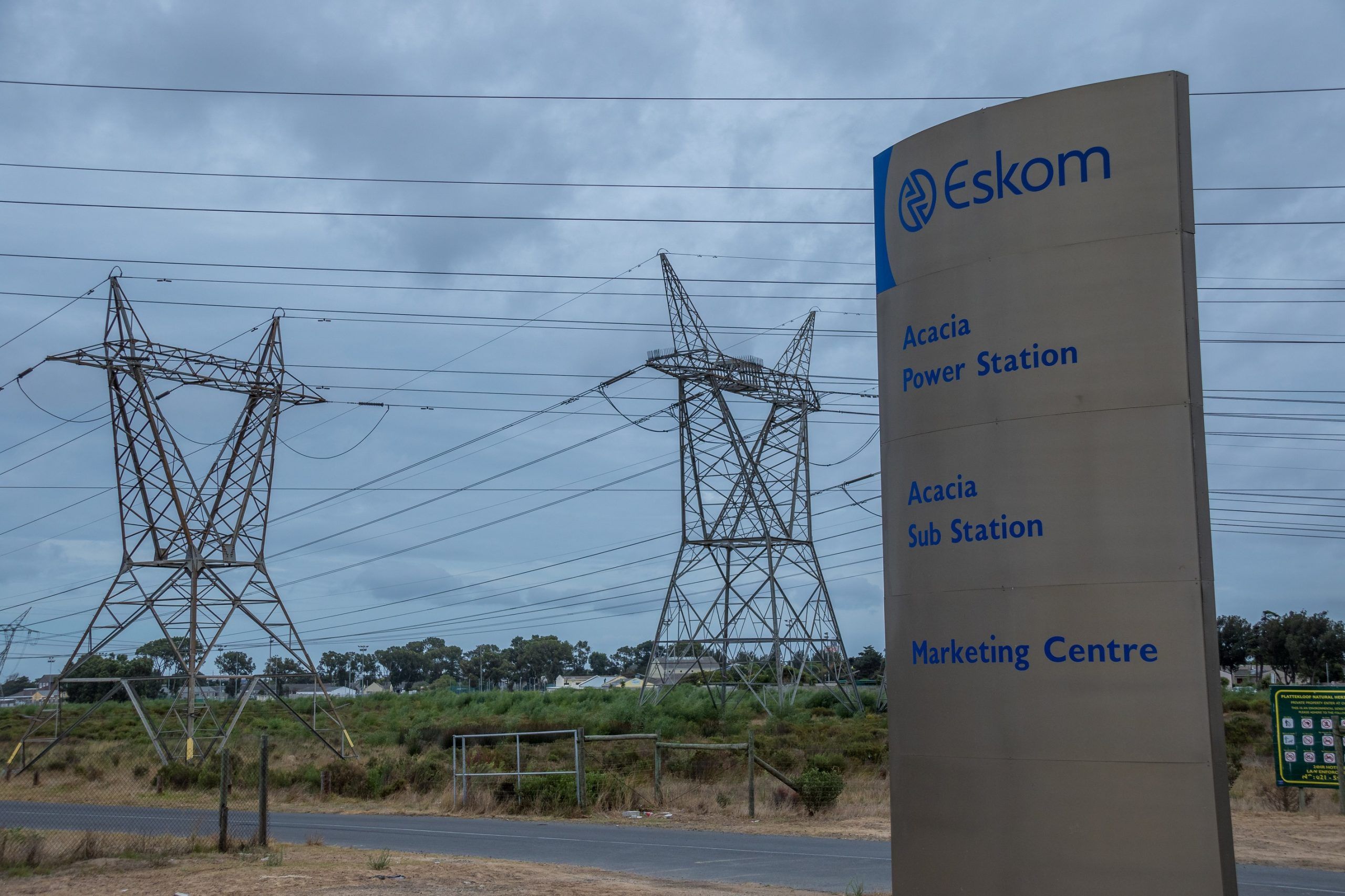

It’s nothing new – the country has suffered power outages for more than a decade – but it has got worse of late. The country’s state-owned power company, Eskom is riddled with debt, has old infrastructure, power stations that do not work properly and was recently crippled by a strike.

South Africa relies on aging coal-fired power stations for most of its electricity. In 2020, just 7% of its energy came from renewable sources, according to the International Energy Agency.

South Africans faced electricity cuts for 288 days last year, while this year there have been electricity blackouts (effectively rolling power cuts) affecting households and businesses for up to ten hours a day as grid operators carry out so-called load-shedding – regular periods of shutting down supply to save energy.

Ajay Gupta, a country analyst with research and analysis company GlobalData – Just Food’s parent company – sums it up: “It is quite visible that the country is struggling with load-shedding along with increasing unemployment and rising inflation which is negatively affecting all areas of business and industry.”

Simply put, South Africa is in the midst of an energy crisis, which is limiting the available supply of electricity.

It’s nothing new – the country has suffered power outages for more than a decade – but it has got worse of late. The country’s state-owned power company, Eskom is riddled with debt, has old infrastructure, power stations that do not work properly and was recently crippled by a strike.

South Africa relies on aging coal-fired power stations for most of its electricity. In 2020, just 7% of its energy came from renewable sources, according to the International Energy Agency.

South Africans faced electricity cuts for 288 days last year, while this year there have been electricity blackouts (effectively rolling power cuts) affecting households and businesses for up to ten hours a day as grid operators carry out so-called load-shedding – regular periods of shutting down supply to save energy.

Ajay Gupta, a country analyst with research and analysis company GlobalData – Just Food’s parent company – sums it up: “It is quite visible that the country is struggling with load-shedding along with increasing unemployment and rising inflation which is negatively affecting all areas of business and industry.”

South Africa’s leader, President Cyril Ramaphosa, declared a state of disaster earlier this year to try and tackle the crisis and has appointed a minister of electricity who has the daunting task of formulating a response to the emergency.

Addressing the nation, Ramaphosa said: “We must act to lessen the impact of the crisis on farmers, on small businesses, on our water infrastructure, on our transport network and a number of other areas and facilities that support our people’s lives.”

The Consumer Goods Council of South Africa (CGCSA) sent the president an open letter calling for government action to support the food and beverage industry.

However, things could get worse on the energy front before they get better.

Eskom so far has not gone beyond stage six power cuts, which require 6,000 megawatts (MW) to be shed from the national grid. However, the company has said it may have to move to stage eight, which would require up to 8,000MW to be shed, translating to 16 hours of outages in a 32-hour cycle, because of increased demand in the winter months. Winter started this month in the southern hemisphere.

Read More

)

)

)